NYC, A Return to the 70s

Going out with my camera on New York City’s streets these days transports me to the 1970s. When we think about New York City during the seventies, imagery comes to mind of a city undergoing unparalleled transformation fueled by economic collapse and rampant crime. We idealize it as a harsh time for the city but a terrific environment for the emergence of counter culture movements and creativity which has given the city the recognition and name that it has today. While John Cassavetes was taking advantage of this magnificent and contradictory natural set creating films such as Gloria, a new generation of would-be rock stars, artists, dancers, and actors freely walked the streets, squatted, or paid almost no rent.

According to Phoebe Hoban, in her biography of Jean Michel Basquiat "A Quick Killing in Art,” Viking 1998; “Influenced by the Punk movement in England, wildly coiffed young people with multicolored Mohawks and safety-pinned clothes seemed to have taken over the Lower East Side- then still a scary neighborhood full of shooting galleries. CBGB's on the Bowery became a mecca for the new bands: the Ramones, Television, the Talking Heads. Punk-rock boutiques began popping up around St. Mark's Place. The city was an urban frontier, theirs for the taking.”

During the seventies, it was still possible to find cheap apartments in Alphabet City (a part of today's gentrified East Village, where currently the average rent is about $3,500 for a one bedroom apartment). By the end of the seventies the homeless population was around 2,000, compared to over 55,000 people sleeping in shelters today, according to the Coalition for the Homeless.

14th Street, Chelsea.

But what specifically about New York City today resembles the seventies? Don’t get me wrong, I understand that the seventies will never come back, and the New York of today lacks many of the underground spaces where independent manifestation of arts thrived. I'm talking fundamentally in an aesthetic meaning and perhaps in a cultural meaning as well. As in the seventies, today, the city is going through a particular transformation. This transformation is starting with the population that is leaving (firstly, the rich --who may come back when the storm passes-- and then the young adventurous in search of the American dream, who recently lost their jobs because of the pandemic and will probably never come back).

According to the New York Times, “The pandemic sent many New Yorkers packing. Almost 50% of rich people have left the city, at least temporarily. In just two months. “New York City businesses that rely on young workers have shed hundreds of thousands of jobs. Restaurants, including some that made New York a culinary destination, have shuttered. Museums are closed. Broadway may not reopen until 2021. In 2 months, arts and entertainment businesses in New York City laid off more than 65,000 people, almost 80% percent of its workforce, according to the city comptroller. Only dine-in restaurants let go of more employees: 119,000.”

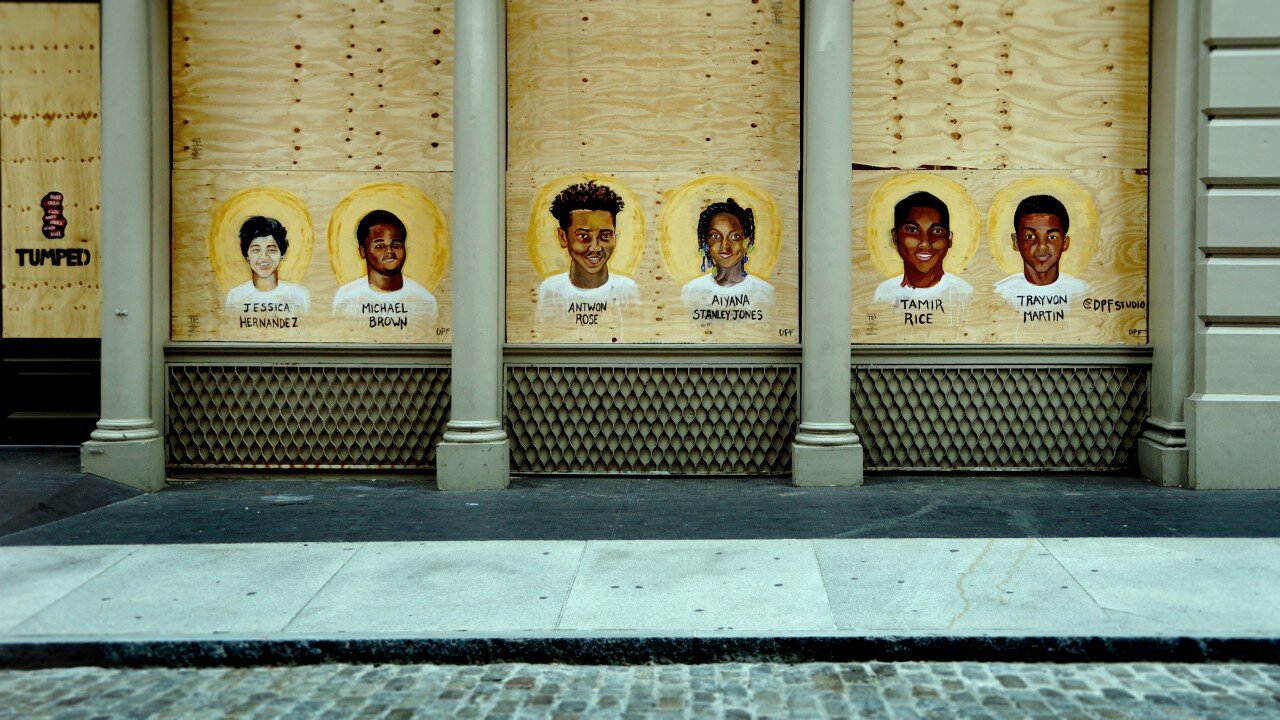

As a result, what we can see in New York City’s streets today are essential workers, less than half of the city's office workers, and a harsh reality of park bench people all around the city. Due to the long time closures resulting from the pandemic and most recently the civil unrest following the murder of George Floyd, storefronts have been protected with wood panels to avoid looting and by doing so owners have given graffiti artists a huge outdoor gallery to play. This last point is bad for consumerism, but represents a painful, yet positive purge for the city. It reminds us that many artists (especially those who exercise art as a form of cultural manifestation and activism) are still living and creating here.

Another point that brings some similarities from the seventies to the current situation of New York City is the constant fear of bankruptcy. In March New York City collected $118 million in real estate property transfer taxes, according to the New York City Independent Budget Office. That figure plummeted to $43 million in April and then to $34 million in May. Taxable real estate sales are projected to drop by more than one-third to $65 billion in 2020, and are not expected to approach pre-pandemic levels until 2024. The city is not collecting enough to provide its citizens with basic services, something which is noticeable today in social services, education, sanitation and public transportation.

Bowery St. Lower East Side. Mid 70s. Photo by Meryl Meisler.

Revolutions Happen During Times of Crisis

In contrast to a regular summer in New York City, this year there are no Summerstage and big outdoor events for social gathering. Instead there are protests every single day, many times a day, ignited after the death of George Floyd by the hands of a white officer in Minneapolis at the end of May. Despite the lack of spaces for social interaction, the protests demanding racial justice are giving the city the revolutionary spirit from the sixties and seventies. The uniqueness of our time is that we’ve never seen protests like these before. Last Friday, during the celebration of Juneteenh, a day which commemorates the end of slavery 155 years ago, the city held massive protests throughout all five boroughs. In the afternoon, more than 20.000 people peacefully marched from Lower Manhattan to Times Square.

BLM Protest in Washington Square Park. Photo by Pablo Herrera.

After a long time of sleepy consumerism, New York City now, more resembles a “real city” than the huge shopping mall that never sleeps. What I feel is far from nostalgia. In less than 4 months, the city has become a place for its citizens and for their voices to be heard. It is comforting to get up in the morning and see people protesting. Go outside in the afternoon and see more people protesting. It is hopeful to hear people screaming for change because it reminds us that people care about social and racial justice. It reminds us that things are not going well in many ways and that we are not relying on the political class to propel and execute the critical changes that our society needs to be better, fair and equal. Until last January we were living anesthetized in an ultra-consuming society that made us believe that everybody was the same and that we all had the same opportunities. That was a total fabrication and to be honest I’m finally glad that things blew-up a bit. Assuming the real and painful situation that many of us are having to live, lose a job, a loved one or to be treated with brutality and injustice, I feel more positive now than I did 4 months ago. At this point the Revolution is happening as it should, from the bottom up, and it is going viral.

BLM Protest in Washington Square Park. Photo by Pablo Herrera.

SoHo is Reclaimed by Artists

One of the most vivid examples of liberation that we are experiencing in New York City today can be seen in SoHo. This neighborhood in Lower Manhattan (which name refers to the area "South of Houston Street") was once the epicenter of independent art in New York City and converted into a big outdoor shopping mall after the eighties. The area's history is an archetypal example of inner-city regeneration and gentrification, encompassing socioeconomic, cultural, political, and architectural “developments.” During the weeks that followed the death of George Floyd, SoHo was looted. It was not a surprise. After the seventies, SoHo became a symbol of the white patriarchal society. Fortunately today, SoHo has been reclaimed by graffiti artists since the pandemic started 3 months ago and especially during and after the weeks that followed the death of George Floyd.

Phoebe Hoban wrote about ShoHo in 1998, “Before 1979 SoHo was still full of textile outlets and floor-sanding companies and lofts that artists could live in under the “Artist in Residence” rental regulations. Despite the growing artist population, by Fifty-seventh Street gallery standards, the neighborhood was still practically the Wild West. But by 1979, when Julian Schnabel, one of the first Neo-Expressionist art stars, had his first show at the Mary Boone Gallery on West Broadway, the cross-pollination between the East Village and SoHo was in full bloom. Within the next few years, SoHo would evolve into the Madison Avenue of the downtown scene.”

Graffiti art in SoHo. Photo by Pablo Herrera.

Among the artists that emerged during the late seventies, the story of Jean Michel Basquiat is what best espouses the dichotomy of a culture that as Phoebe Hoban wrote “continually cannibalizes itself.” Born in New York in 1960, Jean-Michel Basquiat shot to fame in the art world during the 1980s. Initially a graffiti artist, Basquiat’s energetic art drew inspiration from his mixed Haitian and Puerto Rican heritage and black cultural heroes, creating in his paintings a distinctive and subversive visual language.

Graffiti art in Soho. Photo by Pablo Herrera.

By early 1979, Jean-Michel Basquiat had established himself as an artistic persona with SAMO, the author of cryptic sayings scrawled on public spaces all over Manhattan, including, strategically, near SoHo's newest galleries. It was the beginning of his art career and it segued neatly into the "discovery" of graffiti. Ultimately, Basquiat would be the only black artist to survive the graffiti label, and find a permanent place as a black painter in a white art world. Basquiat used social commentary in his paintings as a tool for introspection and for identifying with his experiences in the black community of his time, as well as attacks on power structures and systems of racism. Basquiat's visual poetry was acutely political and direct in its criticism of colonialism and support for class struggle. Basquiat died of a heroin overdose in his art studio at the age of 27.

Phoebe Hoban defines the story of Jean-Michel Basquiat as “a story of life and death tread that peculiarly American line where tabloid meets tragedy. Precisely what energized his art made it impossible for him to survive the system dominated by white people.”

A frame of the film “Downtown 81” with Jean-Michel Basquiat, shot in 1980-1981, directed by Edo Bertoglio.

But the story of Jean-Michel Basquiat is paradoxically the story of New York City itself, a place which consumes itself. The city is not today what it was 4 months ago. I certainly hope the city won’t be the same a few months from now. What I prefer is a city for its citizens rather than investors, with less makeup and more quirks and fresh authenticity. But, I have to ask - how long is it going to take for New York City to again be the place which runs away from its citizens?

Photo Credits:

· Protests in Manhattan and SoHo Graffiti Art by Pablo Herrera

· Lower East Side during the 70s by Meryl Meisler

· A frame of the film “Downtown 81” with Jean-Michel Basquiat, shot in 1980-1981, directed by Edo Bertoglio